Talking about death remains one of society’s great taboos; people decline to discuss the subject even with their closest relatives. Perhaps because of this, very little research has actually been done into how social attitudes towards death and dying vary between generations and between social, ethnic and religious groups.

Difficult as it may be to discuss, the topic is becoming increasingly relevant as space constraints and an ageing society change how families, and the country as a whole, tackles death and funeral arrangements.

“Apart from the traditionally-held notions, there’s almost no or too little formal study of local attitudes towards death and dying, especially with Singapore’s rapidly ageing society,” says Rosie Ching, senior lecturer of statistics at Singapore Management University’s (SMU) School of Economics.

Rosie Ching at the finale presentation

Teaming up with Direct Funeral Services in STAT 101

Working with more than 170 of the students in her Introductory Statistics course, Ching created a survey to examine these attitudes. To lighten the sombre tone of the study, she added components looking at birth and marriage, titling the overall research Hatch.Match.Despatch to reflect the circle of life.

For the ‘Despatch’ element, Ching collaborated with Direct Funeral Services, a local funeral company whose founder Roland Tay became famous for his philanthropic efforts in helping underprivileged families and the victims of crime to hold funerals. His daughter, Jenny Tay, now runs the company with her husband Darren Cheng, and works to abolish the taboos around death and dying. Cheng and Tay helped to formulate the survey questions, and spoke with the students as they conducted their research.

Left to right: Darren Cheng, Jenny Tay and Roland Tay (Source: social sciences student Theodora Ng, working on this project in her freshman year has left a deeply rewarding impression:

“While most of my other friends are stuck solving questions about the probabilities of hypothetical apples being picked from hypothetical baskets, Ms Ching’s project and classes teach us to look at how statistics play out in the real world. Through the project, we got to better understand what Singaporeans’ sentiments were about life and death. Being given the opportunity to sift through mountains of raw data not only gave us a taste of highly sought-after data analysis skills, but the critical thinking skills required to make meaningful sense of the onslaught of numbers.”

Senior lecturer Rosie Ching (right, seated) with her students, including Theodora Ng (left, front)

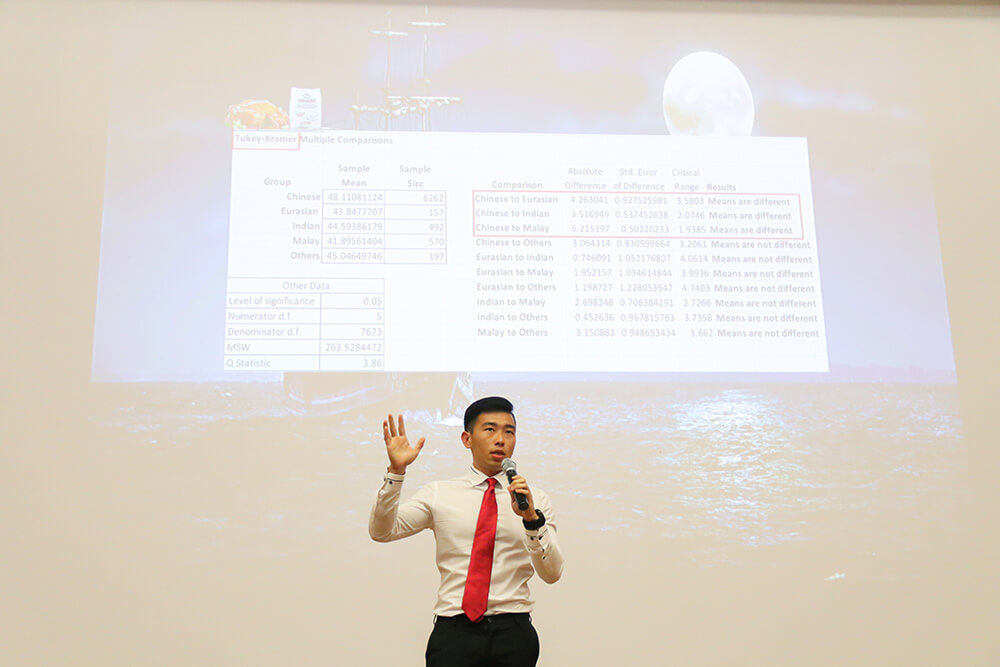

Finale presentation with guest-of-honour Darren Cheng

Surprising results

The study targeted three age groups: under-30s, 30-to-59-year-olds, and 60-and-above, asking over 60 questions of more than 7,500 survey respondents from a broad range of social and ethnic backgrounds. The data collected were then analysed to create Singapore’s first “end-of-life index”, or ELI, which ranks on a scale of 0–100 how open an individual is when it comes to thinking about their end-of-life affairs.

When it came to comparing genders, the results showed that women scored marginally higher than men on the ELI index. Ching shares how Direct Funeral Services’ Jenny Tay had, at the initial phase of the study, raised the observation that female interns seemed far more engaged and less fearful than male interns.

“Our findings statistically verified her observation,” says Ching.

When asked about the possible explanations for these figures, she surmised, “Throughout history, whether at home or in hospitals, end-of-life care traditionally falls in the distaff domain. Women have always been pivotal in caring and nurturing for the home, the sick. They tend to exhibit more empathy and a deeper emotional connection, which could contribute to their higher ELIs.”

And while the results showed that older generations scored slightly lower on the ELI index, the differences between age groups was, surprisingly, not as significant as Ching expected.

“The most compelling finding was that all age groups fell below the 50 mark,” she says. “I had always thought the younger generation would be open to end-of-life affairs, in which case college-goers would have evinced a higher ELI than those in and beyond their 60s. It turns out that all ELI averages stood below 50, though the ELIs did gently fall with rising age. It shows that we have a way to go still in grappling with conservative attitudes towards preparing for death and dying.”

Breaking the taboo behind end-of-life planning

This has implications for policymakers and society at large. Singapore’s population is ageing rapidly. The number of Singaporeans aged over-65 will double by 2030, according to government statistics. By 2050, almost half of the country’s population will be over 65. Even though many Singaporeans are cognisant of this trend, Ching believes that few have actually taken steps to manage their own affairs as they and their relatives age.

“I think it’s still a relatively small proportion of Singaporeans who would take active steps towards preparing end-of-life affairs like a [lasting power of attorney] or [advanced medical directive],” she says, referring to two legal documents which allow an individual to sign over responsibility for their care if they become unable to make decisions for themselves.

“This may raise conflict within families should loved ones be taken ill and little was known or communicated regarding the patient’s wishes. With this in mind and also the results from the study, I think that we need to inculcate in our young, in schools’ education curriculums, topics beginning from birth to growth, health, death with so much to teach, learn and discuss,” Ching says.

“At the same time, with our rapidly ageing society, it is timely to open up a continuing national dialogue on being active and ready for death as a natural progression from life. There has been much focus through the years on ageing gracefully, living well the silver years, what one needs to do to live productively, but in comparison, too little emphasis on what would be highly recommended to do in order to die well.”